Market Matters – The Rally Is Intact, Even If the Week Felt Anything But

It should have been a cleaner week than this. The longest US government shutdown in history is finally over, the lights are coming back on across Washington, and the world’s biggest economy can go back to collecting and publishing the data everyone has been guessing at for six weeks. In theory, that ought to mean less uncertainty and calmer markets. In practice, it hasn’t felt like that at all. I am concentrating on the US and UK this week, with due apologies to the other regions, where things have been largely quiet.

Instead, equities lurched through another bout of AI-led turbulence. After one of the worst single sessions since April, the Nasdaq spent Friday clawing its way back into positive territory, helped by a rebound in the very names that had been hit hardest the day before. Nvidia, Oracle, Palantir and Tesla all staged partial recoveries. Still, the pattern now looks familiar: abrupt intraday swings, sharp factor rotations, and a market that can’t quite decide whether to lean into the AI story or take some money off the table as year-end approaches.

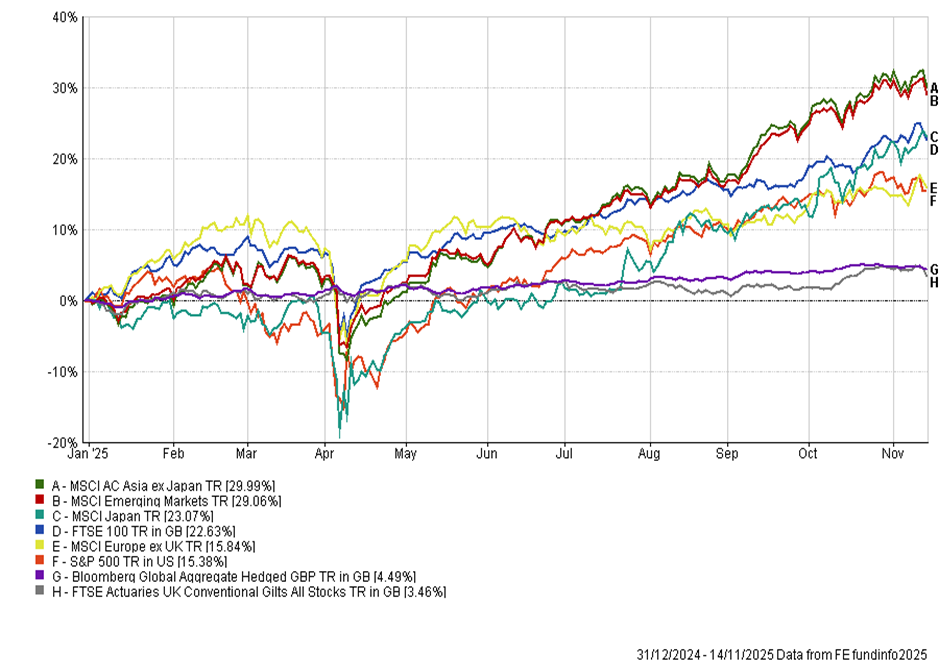

Yet when you step back from the noise of the week, the bigger picture is far less dramatic. Global equity markets remain comfortably positive year-to-date, and leadership remains broadly consistent with the themes that have defined 2023. Asia ex-Japan and Emerging Markets continue to sit near the top of the leaderboard. Japan and Europe have delivered steady, mid-teens gains. And the US — despite the volatility in big tech — remains up by double digits, supported by strong earnings, resilient employment, and the enduring pull of AI-related growth.

Even fixed income, while more subdued, has stabilised after the rate-driven turbulence of early spring. Global aggregate bonds are modestly positive for the year, while UK gilts remain under pressure, but we await the Autumn Budget. What we’ve seen over the past week is less a collapse in sentiment and more a bout of fatigue inside an otherwise solid year. With markets having banked large gains — and with AI valuations stretched — investors are becoming quicker to de-risk in the face of bad news and quicker to rotate when narratives shift. In my view, the underlying trend still points higher. And for anyone considering stepping off here, the harder question is what catalyst would convincingly draw you back in if the rally resumes.

United States – The Fed Takes Centre Stage Again

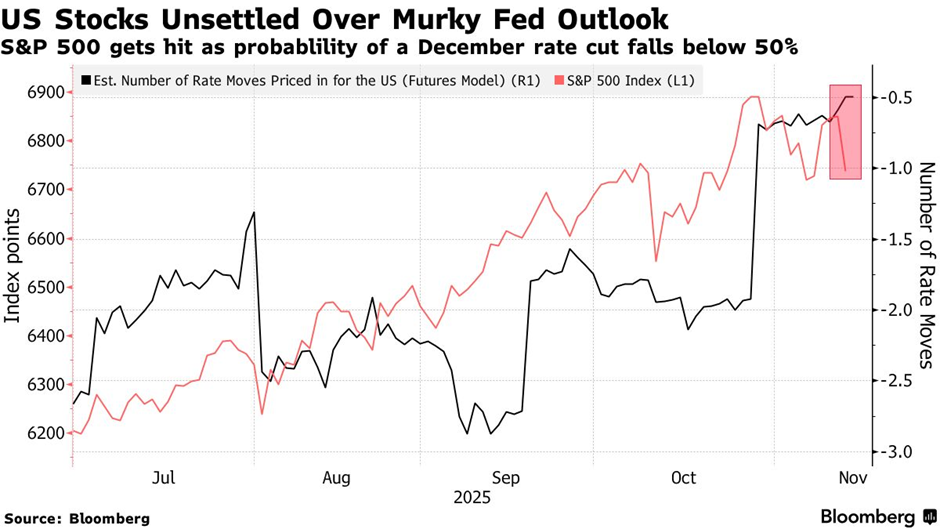

If there was a single thread running through last week’s volatility, it was the market’s growing discomfort with the Federal Reserve’s recent tone. The probability of a December rate cut has fallen sharply, with markets now pricing only a roughly even chance after sitting well above 70% earlier in the week and over 90% a month ago. Several Fed officials have questioned the need for further easing. With official data missing during the shutdown, investors are left to debate whether the Fed is responding to stubborn inflation or cooling labour demand.

That uncertainty hit the interest-rate-sensitive parts of the equity market the hardest. High-momentum stocks, which depend on low discount rates to justify elevated valuations, suffered their worst day since April. Many of the names caught in this downdraft were closely tied to the AI theme. As expectations for rapid rate cuts faded, the valuations of these companies adjusted quickly, triggering broad profit-taking across the sector.

Retail-driven and speculative corners of the market saw even sharper moves. Indicators of retail activity have declined, and baskets tied to meme stocks, crypto miners, and high-beta technology names have delivered some of their steepest declines of the year. Even the market’s most-shorted stocks were hit, a sign that risk appetite pulled back across styles rather than just within the large-cap technology complex.

In the background sits the funding picture, which is becoming increasingly important. AI capital expenditure continues to surge, which is positive for long-term growth but expensive to finance. Oracle’s widening credit spreads last week served as a reminder that ambitious AI investment plans rely heavily on bond markets that are becoming more cautious. Credit investors are signalling that while the AI story is compelling, the pace of balance-sheet expansion now matters.

The end of the forty-three-day government shutdown added yet another layer of complication. In theory, this should help restore visibility, since federal agencies can resume publishing the economic data that markets rely on. In practice, much of the October data will never be collected, and releases in the weeks ahead will come with a wide margin of uncertainty. The shutdown also affected liquidity. With federal payments halted, the US Treasury General Account at the Federal Reserve grew unusually large, effectively withholding cash from the financial system. Now that government spending has resumed, the TGA should start to draw down again, gradually releasing liquidity back into bank reserves and money markets. However, the effects will take time to filter through.

Trump Tariff U-turn?

The combination of a more cautious Federal Reserve, patchy liquidity and the lingering data fog left The combination of a more cautious Federal Reserve, patchy liquidity and the lingering data fog left markets feeling heavier than the headlines might suggest. And just as investors were digesting that mix of macro uncertainty, the political noise picked up again. With the shutdown finally over and consumer frustration still running high, President Trump moved quickly to reinsert himself into the economic conversation this time by shifting tack on trade.

Never a man to shun the limelight, Trump unveiled a raft of tariff reductions on everyday food imports. The move was pitched as an affordability measure aimed at easing grocery prices. Still, it also served as a tacit admission that some of the administration’s own levies have fed directly into the inflation pressures now hurting household sentiment. Coffee, beef, tomatoes and bananas were all granted exemptions, along with a long list of tropical goods the US cannot produce in meaningful quantities. It is probably a very timely move politically, and it will help alleviate inflationary pressures to some degree

United Kingdom – Flat Economy, meet a Budget in disarray!

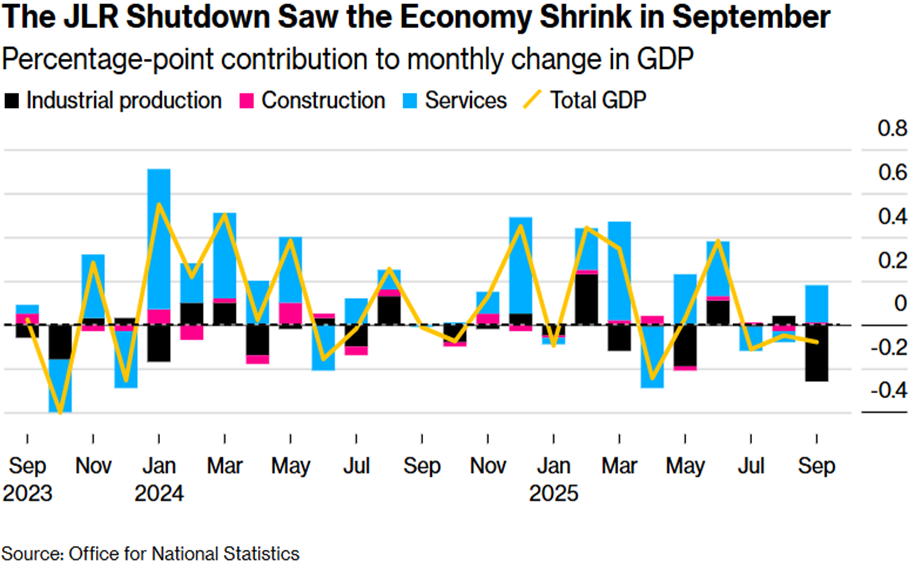

The UK economy stalled almost entirely in the third quarter, with GDP rising by just 0.1%. Most of that disappointment stemmed from September’s contraction, when the Jaguar Land Rover cyberattack led to a five-week shutdown of the country’s largest automaker. Car production fell by almost 30%, marking its worst month since the pandemic, and dragging manufacturing and industrial output sharply lower. Services held up reasonably well, but not enough to offset the damage.

Viewed in isolation, the JLR shock is a one-off. The broader picture, however, is not much brighter. Households and businesses have become noticeably more cautious ahead of the Labour government’s 26th November budget, and surveys show mounting concern over the prospect of higher taxes. Business investment has now fallen for two consecutive quarters, household spending is subdued, and GDP per capita has failed to grow for the first time in nearly two years. Britain has slipped back into the slow lane after its brief spell of outperformance earlier in the year.

If anything, the weakest part of the UK story this week came not from the data but from the politics around the budget itself. The government’s flagship proposal to raise income tax rates — a move that would have broken Labour’s key election pledge — was abruptly abandoned after days of disorderly leaks, counter-briefings and open cabinet dissent. Gilts sold off sharply at the open as investors questioned how the revenue gap would be filled, with ten-year yields jumping to 4.57% before later retracing. Sterling was the weakest major currency on the day.

The problem is not simply the U-turn. It is the sense that Downing Street has lost control of the narrative. Reports suggest Reeves had effectively been running two parallel budgets: one built around headline tax rises and another built around a patchwork of smaller measures. Both factions within Labour reportedly fought ferociously over the shape of the final package, and the result has been confusion, delay and a deterioration in market confidence. Polling now shows that only a small minority of the public believes the government is handling the budget process well.

This political instability sits uncomfortably beside an economy that is already weakening. Exports to the United States are at their lowest level since 2022, due to the tariff measures imposed earlier this year.

Consumer sentiment remains fragile. The labour market is softening. And with the Bank of England signalling that inflation risks have eased and unemployment is drifting higher, traders now assign more than an 80% chance of a rate cut in December.

Investors will tolerate slow growth. What they dislike is uncertainty. The upcoming budget, therefore, matters not only for its fiscal measures but also for whether the government can demonstrate that it is capable of delivering a coherent plan. For now, the impression is of a leadership juggling political factions while the economy drifts sideways.

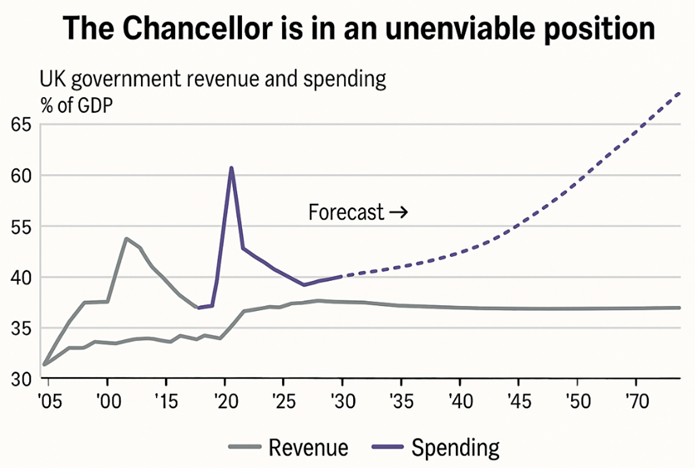

What the UK should be doing — and why a Labour government won’t

I am not a political animal, but the uncomfortable truth laid bare by the fiscal charts is that the UK’s problem is not revenue, it’s spending. Successive governments have allowed the structural cost base of the state to drift higher — driven by demographics, welfare, the NHS, pensions, and debt servicing — while hoping that incremental tax tweaks could paper over the gap. That simply doesn’t work anymore. Spending is on a steep, long-term upward trajectory; revenues are already close to their practical ceiling

Source: JPMorgan

A serious strategy would involve confronting the real drivers of the fiscal imbalance: a long-term plan for health and social care demand, tighter control of departmental spending, a redesign of welfare incentives, more efficient procurement, a credible productivity strategy, and a hard conversation about what the state can realistically provide. None of this is rocket science — it’s just politically radioactive.

Unfortunately, Labour’s voter base is concentrated among public-sector unions, NHS workers, welfare-adjacent groups and middle-income earners who benefit most from large, universal services. These are precisely the constituencies that would resist the reforms the fiscal arithmetic demands. Instead of addressing the spending side, the government is leaning toward stealthier approaches, including frozen thresholds, “smorgasbord” micro-taxes, tweaks to allowances, targeted levies, and the quiet erosion of real incomes. The problem is that these measures only raise small sums while adding more complexity and further damaging business confidence.

Those with the broadest shoulders…

Meanwhile, the top 10% of earners already pay more than half of all UK income tax — and the top 1% carry an extraordinary share of the burden. As the saying goes, those with broad shoulders also have legs — and they can move. You cannot plug a £20–35bn fiscal hole by “taxing the rich” because the rich are the tax base. Push that base too hard and it walks: capital relocates, investment slows, high earners change residency, and the taxable pie shrinks further.

Markets understand this arithmetic far better than the Westminster government. Gilt yields have already reacted because investors can see the structural mismatch that the government is unwilling to confront. If spending is untouchable and broad-based tax rises are politically impossible, then something eventually gives — either growth, fiscal credibility, or market confidence. Labour won’t say this out loud, but the mathematics is increasingly unforgiving, and markets are starting to price that in.

The one relatively bright spot is UK equities. Large-cap UK stocks remain structurally cheap, highly cash-generative and overwhelmingly international in their earnings mix. Around three-quarters of FTSE 100 revenues come from overseas, meaning domestic fiscal turbulence doesn’t thoroughly contaminate corporate performance. A weaker sterling even flatters those overseas earnings. Add in depressed valuations, solid dividend cover and a steady ramp-up in buybacks, and the UK equity market looks better insulated than the political headlines would suggest. Fiscal credibility may be wobbling, but the equity opportunity set is constructive.

This week…

The coming week will help determine whether this latest bout of volatility is just AI fatigue or something more widespread. The big event is Nvidia’s earnings on Wednesday, which have become the market’s de facto referendum on the entire AI trade. With sentiment already shaky after recent tech swings, any hint of softer data-centre demand or slower capital expenditure could reverberate well beyond the stock itself.

The macro calendar also begins to normalise now that the shutdown is over. We’ll receive the Fed minutes, a catch-up run of delayed US data, and the final Michigan sentiment reading, all of which should provide a clearer signal on whether the case for a December rate cut is firming again or still weakening.

Internationally, flash PMIs for the US, the eurozone, and the UK will provide an updated read on global growth momentum heading into year-end. China will also drip out further data points, which remain essential for gauging whether domestic demand is stabilising after the recent export wobble.

In short, markets are not short of catalysts: Nvidia mid-week, a backlog of US data attempting to re-establish the trend, and a global PMI pulse check to finish. Volatility may not disappear immediately, but the fog should thin.

DOWNLOADS

There are currently no downloads associated with this article.