Lessons From France and the US: What the UK Structured Products Market Can Learn

The UK once played a meaningful role in the development of retail structured investments; it now lags its peers — raising the question of whether the regulatory and distribution framework has become overly restrictive. Over the past few decades, structured products have grown into a mainstream investment tool in several major markets. Our European neighbours utilise the merits of these investments to a far greater degree. In France, for example, they form a core part of retail and private banking portfolios. And over the pond, in the United States, issuance of structured notes has expanded rapidly, supported by adviser platforms and a disclosure-based regulatory regime. By contrast, the UK structured products market remains comparatively small, and its growth seemingly stuck in the doldrums.

Taking France as a case study, at a high level, the contrast is stark. The UK’s nearest European peer, both in geographic proximity and economic stature, consistently records tens of billions of euros in annual structured product issuance, much of it distributed to retail investors through domestic banks and insurance wrappers. And in the US, the structured notes market has grown even faster, reaching record issuance levels in recent years as advisers and institutions increasingly use structured notes for yield enhancement and risk shaping. The UK, by comparison, has a modest retail market, dominated by a narrow set of products and largely absent from the growth trends seen elsewhere.

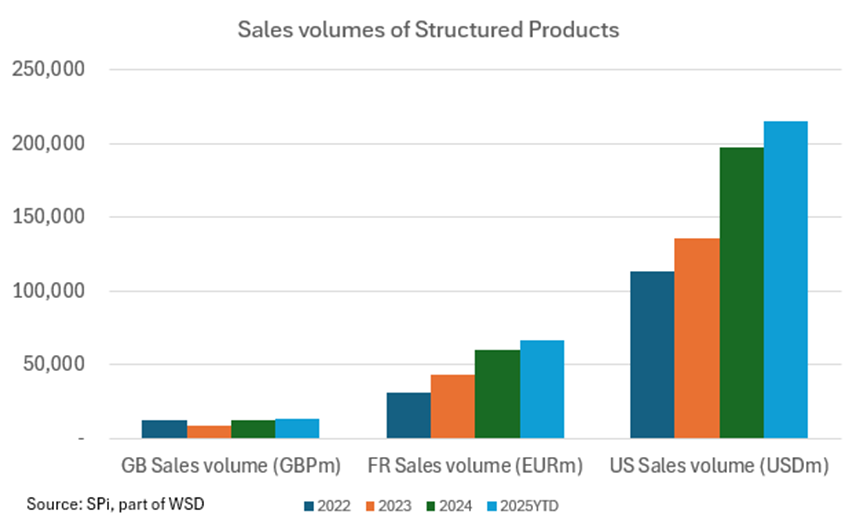

The chart below illustrates issuance volumes over the past four years. Adjusted for inflation, the UK market contracted, while France and the US experienced growth of 113% and 89%, respectively.

The reasons for this divergence are not primarily economic. Market volatility, interest rates, and investor demand for income have broadly favoured structured products across all three jurisdictions. Instead, the explanation lies in regulation, distribution, and market culture — particularly the way structured products are perceived and governed in the UK.

The UK regulatory response to structured products has been shaped heavily by decades old mis-selling scandals. In the years following the global financial crisis, regulators took a deliberately conservative approach, emphasising investor protection, product governance, and adviser accountability. These reforms were well-intentioned and, in many respects, justified. However, they also had second-order effects. Complex products became associated with heightened compliance risk, long-tail liability, and reputational damage for advisers.

As a result, independent financial advisers (IFAs) — the dominant retail distribution channel in the UK — have largely stepped back from structured products. For many advisers, the risk of future complaints or regulatory scrutiny outweighs the perceived benefit of using such instruments, even when the products themselves are relatively straightforward. This has created a self-reinforcing cycle: limited adviser demand reduces issuer innovation and scale, which in turn keeps the market small and conservative.

Ironically, the UK structured products market is already highly standardised. The vast majority of retail issuance consists of relatively simple autocallable notes, often linked to the FTSE 100 or a small basket of large UK equities. These products typically offer predefined coupons, clear downside barriers, and limited structural complexity. In practice, they are often simpler than many products sold widely in France or the US. Yet despite this standardisation, they continue to be treated with a high degree of regulatory caution.

France provides a useful point of comparison. There, structured products are widely distributed by major banks and embedded within insurance and savings structures. Regulation focuses less on discouraging product usage and more on standardisation, disclosure, and consistency. As a result, structured products are viewed as a normal portfolio component rather than an exotic or niche investment. While risks are clearly disclosed, the regulatory framework allows scale, familiarity, and repeat issuance to develop. This, in turn, supports liquidity, pricing efficiency, and investor understanding.

The US approach differs again. Rather than restricting product complexity, US regulation is largely disclosure-based. Investors are permitted access to a wide range of structured notes provided risks are clearly explained and suitability requirements are met. The adviser and platform ecosystem plays a critical role here. Technology-driven platforms have made it easier to compare products, document suitability, and manage lifecycle events. Structured notes are often framed as packaged options strategies — a concept that resonates with a market already comfortable with derivatives, options, and volatility trading.

Against this backdrop, the UK’s stance appears unusually restrictive. Structured products are neither particularly complex nor especially novel relative to global peers, yet they face a level of scrutiny that discourages usage. The result is not a more innovative or diversified market, but a smaller one — dominated by a narrow range of low-risk, low-variety products and limited investor participation.

This raises an important policy question: has the UK over-corrected? Investor protection is essential, but protection that limits access to well-understood tools may ultimately disadvantage investors. Structured products, when properly designed and disclosed, can serve legitimate purposes — income generation, risk management, and portfolio diversification. Preventing their broader use does not eliminate risk; it merely pushes investors toward cruder alternatives or leaves potential opportunities unrealised.

None of this argues for deregulation or a return to past excesses. However, it does suggest that the UK could benefit from recalibrating its approach. Greater emphasis on standardisation, clearer guidance for advisers, and a more proportionate assessment of product risk could help revive a market that has fallen behind its peers. Without such changes, the UK risks remaining an outlier — cautious, constrained, and increasingly disconnected from developments in Europe and the United States.

In a global investment landscape where flexibility and innovation matter, the cost of excessive caution may be higher than it appears.

This material is for information purposes only. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Investments carry a risk to capital and returns are not guaranteed.

DOWNLOADS

There are currently no downloads associated with this article.